Walking With Dinosaurs extends the reach of the incredibly successful BBC television series into feature film territory. Presented in stereoscopic 3D, the Barry Cook-directed film features computer generated animation by Animal Logic. In order to bring multiple species of dinosaurs to life, the studio relied on contributions from several palaeontologists as well as a number of new technical innovations for muscle movement and realizing skin and scales.

Acquiring background plates

As in the TV series, the methodology for making the film was to shoot real background plates and insert CGI dinosaurs. The starting point involved storyboards, which were edited together and developed into further layout and previs. Scouting of locations also took place, with filming occurring in Alaska and New Zealand. The filmmakers collected large-scale LIDAR scans of the environments in the US state. “We worked with WHPacific who traditionally only do engineering-based LIDAR,” says Animal Logic visual effects supervisor Will Reichelt. “They had some amazing equipment that you can strap to the back of a truck and then drive across large areas such as the entire length of a beach, or up the side of a mountain.”

Watch behind the scenes of the shoot for Walking With Dinosaurs.The film was shot with RED EPICs, with some elements filmed on Sony F-23s. The Cameron/Pace Fusion 3-D rig was also used for stereo shots. “We weren’t quite sure how close the elements were going to end up being, so to be safe we ended up bracketing the IO so we had as much depth as we needed to,” says Reichelt. “We found later on that the further back you sit elements in a stereoscopic shot, the less depth you’re going to see. There’s a tipping point where you can just use a monoscopic element – depending on the shot, it could be like 10 or 15 feet back from the camera.”

Some on-location environment interaction was filmed, with Animal Logic instead relying mostly on adding elements such as foot falls, dust hits and tree movement as visual effects particle elements crafted with tools like Houdini. “We would do a setup for a shot and see what could we possibly grab here while we’re in this spot,” notes Reichelt, however. “I had one or two bluescreens and would get the wrangler to plonk them down in a spot and get a bunch of elements such as grass clumps or rocks for sitting the dinosaurs on to the surface. Then for the actual kicks we did all that digitally – sand, dirt, snow – all done with particle effects.”

Character creation – a new muscle system

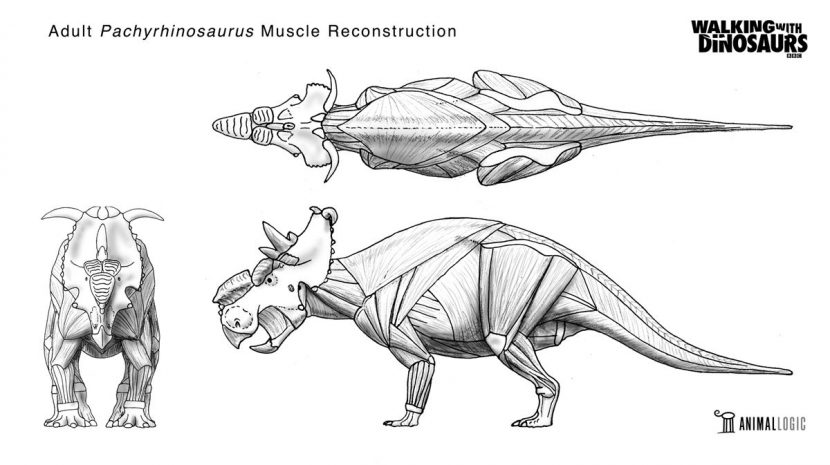

In order to create photorealistic dinosaurs, Animal Logic looked to paleontological research contributed from world experts retained by the BBC. The characters in the film exhibit relationships with each other, but do not talk. In this way, the dinosaurs were not heavily anthropomorphized, which means for modeling and rigging purposes Animal Logic maintained the realism, only pushing movements for certain actions.

In order to animate dinosaurs with the intended realistic motion, Animal Logic developed a new muscle system dubbed Steroid, which, according to Reichelt, was able to “provide interaction between outer skin, the internal fat and muscles and make that more automated for the animators as a simulation so they didn’t have to worry about doing by hand.”

Approved model & walk cycle for the adult Pachyrhinosaurus based on provided paleo reference.It’s very much the next iteration of our muscle system,” adds Animal Logic CG supervisor Emmanuel Blasset. “With our past systems, various muscle groups needed to be triggered by certain poses and calibrated for specific type of animation – walks, runs, flights for owls, and would still require per shot adjustments. With Steroid, we were able to create a very robust system that managed muscles, bones, and skin with very little tweaks beyond the initial setup.”

Character creation – skin and scales

An animated ‘RepTile’ test, using a Gorgosaurus. The skin underneath is coloured to contrast with the scales to show the range of stretch.Along with the new automated muscle system, the dinosaur skin and scales were also elements tackled with a new approach by the Animal Logic team. Having conquered feathers for Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole with its Quill tool, Animal Logic took the grooming approach further for its scales solution known as RepTile. “We didn’t want to paint millions of scales so we developed a procedural system across the body,” states Reichelt. “We can place feature scales, we can arrange filler scales around feature scales. And we can hand paint our own scales in and around all that.”

The initial test of Animal Logic’s proprietary procedural system ‘RepTile’, for creating scales on skin. The test shows a sphere covered in procedural scales, with an animated test of the different properties that can be controlled through the shader (eg base and tip width, height) as well as how each scale is fixed to a point on the skin and will not stretch, even if the underlying skin does.“It really allowed us to iterate major modifications on our characters quickly and achieve very realistic deformations,” says Blasset, “whenever the skin was deforming or sliding on top of a surface we would only notice the skin in between rigid scales stretching and compressing. It created a very subtle yet powerful effect.”

A ‘RepTile’ lighting test, showing additional fine displacement across each scale.Sitting the dinos in the plates

Artists relied on both LIDAR scans of the shooting locations and matchmoving with 3D Equalizer to provide suitable plates to comp the dinosaurs into. One particularly challenging integration effort involved creatures in water. “We were doing LIDAR scans of every single environment,” says Reichelt, “and we just knew that it was going to be an essential tool to getting the dinosaurs to sit in the right depth, especially on an undulating terrain. But you can’t LIDAR water, so we came up with a way of being able to look at the disparity map between the left and right eye and generate a mesh per frame based on that disparity map.” OCULA was also a key tool Animal used to solve stereo issues.

The dinosaurs were rigged and animated in XSI, with rendering taking place in RenderMan. “We had multiple HDRIs and LIDAR for each setup giving us a detailed representation of the shot in its environment for lighting,” explains Blasset. “As a base, thanks to the adoption of a physically plausible lighting and shading, lighters would start with dinosaurs that already feel pretty integrated within the scenery. The lighters can now focus on the artistry of lighting a character as you would with an actor on a real set. Rather than trying to make characters look real, it is all about them look great!”

Watch a breakdown of the forest fire sequence.Compositing was handled in NUKE. For one seemingly effects-heavy sequence – the forest fire – this involved compositing a large number of practical elements. “We decided early on to do the bulk of that practically,” says Reichelt, “as we didn’t want to create a whole forest on fire from just nothing. We worked with the practical effects guys to build a base in the background. We didn’t actually create any CG fire – it was all practical elements or shot in situ. The practical effects guys had a flamethrower which we thought would be cool to shoot in 3D. So we shot a few passes on that, and ended up using it in a couple of shots where the fire completely overtakes a hiding spot.”